If the gospel story were true, it wouldn’t change with time. God’s personality wouldn’t change, God’s plan of salvation wouldn’t change, and the details of the Jesus story wouldn’t change. But the New Testament books themselves document the evolution of the Jesus story. Sort them chronologically to see.

If the gospel story were true, it wouldn’t change with time. God’s personality wouldn’t change, God’s plan of salvation wouldn’t change, and the details of the Jesus story wouldn’t change. But the New Testament books themselves document the evolution of the Jesus story. Sort them chronologically to see.

Paul’s epistles precede Mark, the earliest gospel, by almost 20 years. The only miracle that Paul mentions is the resurrection (1 Cor. 15:4). Were the miracle stories so well known within his different churches that he didn’t need to mention them? It doesn’t look like it.

Jews demand miraculous signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles (1 Cor. 1:22–3).

The Jews demand signs? That’s not a problem. Paul had loads of Jesus miracles to pick from. But wait a minute—if the Jesus story is a stumbling block to miracle-seeking Jews, then Paul must not know of any miracles.

Miracles come later, with the gospels. Looking at them chronologically, notice how the divinity of Jesus evolves. He becomes divine with the baptism in Mark; then in Matthew and Luke, he’s divine at birth; and in John, he’s been divine since the beginning of time.

The four gospels were snapshots of the Jesus story as told in four different communities at four different times. Because the synoptic (“looking in the same direction”) gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke share so much source material, their similarity is not surprising. Nevertheless, 35% of Luke comes uniquely from its community (such as the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son), and 20% of Matthew is unique (such as Jesus and his family fleeing to Egypt after his birth and the zombies that walked after Jesus’s death). And, of course, John is quite different from these three, having Gnostic and (arguably) Marcionite elements.

This synoptic similarity undercuts the argument that the gospels are eyewitness accounts. If the authors of Matthew and Luke were eyewitnesses, why would they copy so heavily from Mark? The authorship question (that Mark really wrote Mark, etc.) that grounds the claims that the gospels record eyewitness history is another tenuous element of the evolving story, as I’ve written before.

The gospels don’t even claim to be eyewitnesses (with the exception of a vague reference in John 21:24, in a chapter that appears to have been added by a later author). And even if they had, would that make a difference? Would tacking on “I Bartholomew was a witness to all that follows” to a gospel story make it more believable?

Would it make the story of Merlin the wizard more believable?

Consider some of the noncanonical gospels that include attributions. “I Simon Peter and Andrew my brother took our nets and went to the sea” is from the Gospel of Peter, and “I Thomas, an Israelite, write you this account” is from the Infancy Gospel of Thomas. These gospels are rejected both by the church and by scholars despite these claims of eyewitness testimony. Why then imagine that the vague “This is the disciple who testifies to these things and who wrote them down; we know that his testimony is true” (John 21:24) adds anything to John?

There are dozens of noncanonical gospels. Christian churches reject these in part because they were written late. But if we agree that the probable second-century authorship for (say) the gospels of Thomas, Judas, and James is a problem because stories change with time, then why do the four canonical gospels get a pass? If the gospel of John, written 60 years after the resurrection, is reliable despite being a preposterous story, why reject Thomas, written just a few decades later?

The answer, it seems, is simply that Thomas doesn’t fit the mold of the version of Christianity that happened to win. History, even the imagined history of religion, is written by the victors.

Read the first post in this series: What Did the Original Books of the Bible Say?

God made everything out of nothing,

but the nothingness shows through

— Paul Valery

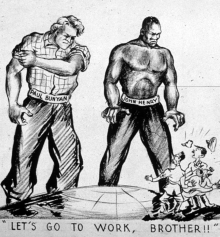

Photo credit: Wikimedia

Related posts:

It’s been a great first year for Cross Examined, but it’s time for a move. This blog is moving to Patheos, one of the largest religion sites on the internet. It has portals featuring material on lots of other religions, including over 100 blogs. I invite you to continue following the blog at the new site.

It’s been a great first year for Cross Examined, but it’s time for a move. This blog is moving to Patheos, one of the largest religion sites on the internet. It has portals featuring material on lots of other religions, including over 100 blogs. I invite you to continue following the blog at the new site.

Almost all of the original apostles that surrounded Jesus died martyr’s deaths. If they knew that he was just a regular guy and that the resurrection story was fiction, why would they go to their deaths supporting it?

Almost all of the original apostles that surrounded Jesus died martyr’s deaths. If they knew that he was just a regular guy and that the resurrection story was fiction, why would they go to their deaths supporting it?

Let’s straighten out some of the terms used in the study of religion, the supernatural, and related topics. I know I’ve not always used the terms precisely, so this is a chance to make amends.

Let’s straighten out some of the terms used in the study of religion, the supernatural, and related topics. I know I’ve not always used the terms precisely, so this is a chance to make amends. I’ve been on the offensive with a

I’ve been on the offensive with a  If the gospel story were true, it wouldn’t change with time. God’s personality wouldn’t change, God’s plan of salvation wouldn’t change, and the details of the Jesus story wouldn’t change. But the New Testament books themselves document the evolution of the Jesus story. Sort them chronologically to see.

If the gospel story were true, it wouldn’t change with time. God’s personality wouldn’t change, God’s plan of salvation wouldn’t change, and the details of the Jesus story wouldn’t change. But the New Testament books themselves document the evolution of the Jesus story. Sort them chronologically to see.