Let’s straighten out some of the terms used in the study of religion, the supernatural, and related topics. I know I’ve not always used the terms precisely, so this is a chance to make amends.

Let’s straighten out some of the terms used in the study of religion, the supernatural, and related topics. I know I’ve not always used the terms precisely, so this is a chance to make amends.

We’ll begin with the big category, folklore. This is the traditional knowledge or forms of expression of a culture passed on from person to person. Folklore can be material (quilts, traditional costumes, recipes, the hex signs on Amish barns, etc.), behavioral (customs such as throwing rice at a wedding, what constitutes good manners, superstitions, etc.), or traditional stories.

Traditional stories is itself a large category, containing music, anecdotes, ghost stories, parables, popular misconceptions, and other things you might not think of.

Now on to the kinds of traditional stories that are most interesting to apologetics. These terms can overlap quite a bit, so consider these definitions approximations. First, let’s consider stories seen as true (or plausibly so) by their hearers.

- Legends are grounded in history and can change over time. They can include miracles. Urban legends are a modern category of legends that don’t include miracles, are set in or near the present day, and take the form of a cautionary tale.

- Myths are sacred narratives that explain some aspect of reality (for example: the myth of Prometheus explains why we have fire and the Genesis creation myth explains where everything came from). Epic poems such as Beowulf and the Odyssey are one kind of myth.

The difference between legends and myths is that a legend is set in a more recent time and generally features human characters, while myths are set in the distant past and have supernatural characters. Some stories are mixtures of the two—the Iliad tells the story of a real city, and the characters include gods, humans with supernatural powers, and ordinary humans.

Lady Godiva, King Arthur, William Tell, and Atlantis are examples of legends—the stories have human characters and are set in a historic past. Myths include the stories of Hercules and Zeus, Hindu mythology, the Noah story, and the creation stories of dozens of cultures—they have gods as characters and are set in a distant or undefined past.

Let’s take a brief detour to look at a few relevant terms that are not part of the category of traditional stories.

- Religion starts with the sacred narratives of mythology and adds beliefs and practices. Myth and scripture are both sacred, but scripture is the writings themselves. Doctrine is codified teaching, and dogma is that mandatory subset of the doctrine that must be believed for one to be a member.

- Superstition is any belief that relies on a supernatural (instead of natural) cause like astrology, omens to predict the future, magic, or witchcraft. It can also be defined as the unfounded supernatural beliefs of the other guy’s religion (not your own, of course). Merriam-Webster defines it as “a belief or practice resulting from ignorance, fear of the unknown, trust in magic or chance, or a false conception of causation.”

Finally, let’s consider stories understood by their hearers to not be true.

- Fables have a particular kind of character: nonhumans such as animals, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that have human-like qualities. Fables end with a moral.

- Fairy tales also have particular characters: fantasy characters such as fairies, goblins, and elves. Magic is also an element. There is no connection with historic time (it begins “Once upon a time …”).

- Parables are plausible stories with plausible characters (no talking rocks, no magic) that are not presented as true. Parables illustrate a moral or religious principle.

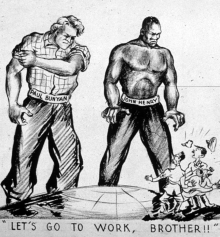

Photo credit: Wikimedia

Related posts:

- See all the definitions in the Cross Examined Glossary.

Related links:

- “Literary or Profane Legends,” New Advent.

Consider this parable:

Consider this parable: