Bill Donohue is president of the Catholic League. I’ve responded before to his hatred of same-sex marriage and his annoyance at the consequences of living with a secular Constitution.

Bill Donohue is president of the Catholic League. I’ve responded before to his hatred of same-sex marriage and his annoyance at the consequences of living with a secular Constitution.

But today Bill is all smiles. With his “Top Religion Story of 2012” he gloats that a new survey (“How America Gives” by the Chronicle of Philanthropy) shows religious Americans to be more generous than their nonreligious neighbors.

[The survey’s] central finding was that the more religious a city or state is, the more charitable it is; conversely, the more secular an area is, the more miserly the people are.

Those good-for-nothing “Nones” (people who check “None of the Above” on the religion survey) and liberals get a well-deserved finger-wagging from Donohue.

[The survey] suggests that the rise of the “nones”—those who have no religious affiliation—are a social liability for the nation. It also shows that those who live in the most liberal areas of the nation are precisely the ones who do the least to combat poverty. They talk a good game—liberals are always screaming about the horrors of poverty—but in the end they find it difficult to open their wallets.

There is little doubt that the “nones” and liberals (there is a lot of overlap) are living off the social capital of the most religious persons in the nation. Perhaps there is some way this can be reflected in the tax code.

Using red/blue distinctions according to how states voted in the 2008 McCain/Obama presidential election, the study says:

Red states are more generous than blue states. The eight states where residents gave the highest share of income to charity went for John McCain in 2008. The seven-lowest ranking states supported Barack Obama.

The Other Side of the Story

But read a little more into the survey, and things look different.

The parts of the country that tend to be more religious are also more generous. … But the generosity ranking changes when religion is taken out of the picture.

Drop religious donations, and the Bible belt drops from the most generous part of the country to the least. This is probably not the point that Donohue meant to make.

But why discard donations to religious organizations? Because, though they’re nonprofits, religious organizations’ charity work (feeding or housing the needy, for example) is negligible. Running the typical church takes most of its income, compared to, say, the comparatively minor 9% overhead for Save the Children or 8% for the American Red Cross. We have only guesses for how much charitable work churches and ministries do since, unlike other nonprofits, their financial records are secret. Some educated guesses place their charity at only 2% of revenue.

(I’ve written more about why churches are more like country clubs than charities and about the embarrassment that churches’ closed-book policy causes them.)

In rough numbers, Americans donate $300 billion per year to nonprofits, and churches get one third of that. With churches passing through as little as a few billion dollars (again, we can only guess) to charities, that is little compared to the $200 billion that Americans give to good-works organizations directly.

The Positive View of the Christian’s Position

Let me try to see things from the Christian’s standpoint. They take pride in the fact that their church donations help the needy. (Ignore for now what fraction passes through.) From their standpoint, they see their money funding church-sponsored soup kitchens or low-income housing. Give credit where it’s due—it’s great that churches pitch in to help. But what about poorer communities where the churches can’t help as much? And what about those atheists who aren’t contributing to churches’ projects—wouldn’t it be nice if they pitched in?

Karl Marx touched on this question of how society should support its needy with his observation that religion is the “opium of the masses.” He wasn’t saying that religion dulls the senses; rather, he meant that it was like medicine—a mechanism for coping with a broken society.

Churches can do good work, but that work is necessary only because society is broken. What if society fixed its own problems rather than leaning on churches (and charity) to plug the leaks?

Donohue said that liberals “talk a good game—[they] are always screaming about the horrors of poverty—but in the end they find it difficult to open their wallets.” We’ve seen that blue regions of the country are actually more generous in individual charity. More to his point, liberals are often eager to see society as a whole contribute more to helping society’s needy. Churches shouldn’t have to step in to fix society’s problems. Society already helps its needy in ways that eclipse the few billion dollars that churches give to charity. $725 billion of our money goes to individuals each year through Social Security and $835 through Medicare and Medicaid. Marx wasn’t right about much, but he was right about this—let’s take his cue, see churches’ good works as noble symptoms of society’s failings, and improve the system.

Another Try at 2012’s Top Story

Donohue may like surveys, but the one he picked seems to have blown up in his face. He does ask a good question, though: what was the top religion story of the year?

- How about polls showing the rapid rise in the population of Nones (“None of the above”) that make that the world’s third largest “religion”?

- Maybe last spring’s Reason Rally of over 20,000 freethinkers on the National Mall, the biggest secular gathering in world history by a factor of ten.

- Or the recent drop in Americans who consider themselves religious, from 73% to 60% in the last eight years.

- Or the strong public support for gay marriage, both in polls (now supported by more than 50% of the public) and in November’s election (for the first time, voters enabled gay marriage in three states, after 32 straight losses in prior elections).

- Or a Gallup poll showing Americans’ confidence in religion at an all-time low.

- Or the black eye the Catholic Church continues to show because of its handling of the priest pedophilia scandals.

- Or maybe studies showing that divorce rates for evangelicals and fundamentalists are the highest in the country, people want less religious talk by politicians, teen mothers come disproportionately from red states, and red states are net takers of federal money and blue states are net givers.

There are lots of interesting stories out there, and these are admittedly just ones that caught my eye. But Donohue’s selection not only didn’t say what he hoped it would say, it was a deck-chairs-on-the-Titanic kind of story. Perhaps the shifts in American religion are more substantial than what he wants to acknowledge.

Ah! what a divine religion might be found out

if charity were really made the principle of it instead of faith.

— Percy Shelley

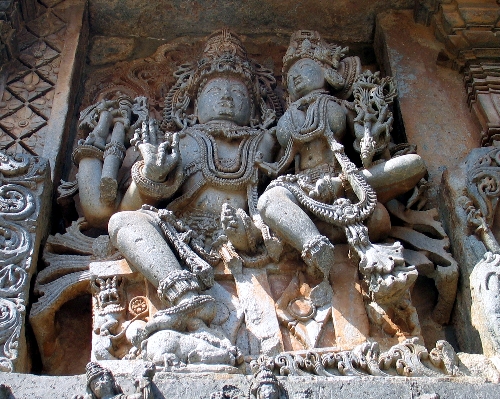

Photo credit: Mike Licht

We’re all familiar with the major astronomical milestones in the year—the summer and winter solstices, when our hemisphere is tipped maximally toward or away from the sun, and the spring and fall equinoxes, when each day worldwide has roughly 12 hours of sunlight and 12 of darkness. These dates separate the seasons—the spring equinox marks the beginning of spring, and so on. They are to the calendar what north, south, east, and west are to the compass.

We’re all familiar with the major astronomical milestones in the year—the summer and winter solstices, when our hemisphere is tipped maximally toward or away from the sun, and the spring and fall equinoxes, when each day worldwide has roughly 12 hours of sunlight and 12 of darkness. These dates separate the seasons—the spring equinox marks the beginning of spring, and so on. They are to the calendar what north, south, east, and west are to the compass.

Bill Donohue is president of the Catholic League. I’ve responded before to his

Bill Donohue is president of the Catholic League. I’ve responded before to his  In the late 1500s, Japan had more guns than any European country, but that ended as Japan entered a self-imposed isolation that lasted over two centuries. This peaceful Tokugawa period was the time of the shoguns and samurai.

In the late 1500s, Japan had more guns than any European country, but that ended as Japan entered a self-imposed isolation that lasted over two centuries. This peaceful Tokugawa period was the time of the shoguns and samurai.