One popular science-y argument for God is that DNA is information. In fact, it’s not only information, it’s a software program. Programs require programmers, and for DNA, this programmer must be God.

For example, Scott Minnich, an associate professor of microbiology and a fellow at the Discovery Institute, said during the 2005 Kitzmiller v. Dover trial, “The sophistication of the information storage system in nucleic acids of RNA and DNA [have] been likened to digital code that surpasses anything that a software engineer at Microsoft at this point can produce.” Stephen Meyer, also of the Discovery Institute, said, “DNA functions like a software program. We know from experience that software comes from programmers.”

Man/machine parallels

But how does DNA brings anything new to the conversation? The idea that the human body is like a designed machine has been in vogue ever since modern machines. The heart is like a pump, nerves are like wires, arteries are like pipes, the digestive system is like a chemical factory, eyes and ears are like cameras and microphones, and so on. We don’t hear, “Animals’ arteries and veins are like the water and drain pipes in a house, so there must be a celestial Plumber!”

I don’t find the celestial Programmer claim much more compelling, but let’s push on and respond to the apologist’s claim that programs (in the form of DNA) require programmers.

Nature vs. machine

As a brief detour, notice how we tell natural and manmade things apart. Nature and human designers typically do things very differently. This excerpt from my book Future Hype: The Myths of Technology Change explores the issue:

By the 1880s, first generation mechanical typesetters were in use. Mark Twain was interested in new technology and invested in the Paige typesetter, backing it against its primary competitor, the Mergenthaler Linotype machine. The Paige was faster and had more capabilities. However, the complicated machine contained 18,000 parts and weighed three tons, making it more expensive and less reliable. As the market battle wore on, Twain sunk more and more money into the project, but it eventually failed in 1894. It did so largely because the machine deliberately mimicked how human typesetters worked instead of taking advantage of the unique ways machines can operate. For example, the Paige machine re-sorted the type from completed print jobs back into bins to be reused. This impressive ability made it compatible with the manual process but very complex. The Linotype neatly cut the Gordian knot by simply melting old type and recasting it. . . .

As with typesetting machines, airplanes also flirted with animal inspiration in their early years. But flapping-wing airplane failures soon yielded to propeller-driven successes. The most efficient machines usually don’t mimic how humans or animals work. Airplanes don’t fly like birds, and submarines don’t swim like fish. Wagons roll rather than walk, and a recorded voice isn’t replayed through an artificial mouth. A washing machine doesn’t use a washboard, and a dishwasher moves the water and not the dishes.

DNA doesn’t look like software

With DNA, we again see the natural vs. manmade distinction. It looks like the kind of good-enough compromise that evolution would create, not like manmade computer software. The cell has no CPU, the part of a computer that executes instructions. Also, engineers have created genetic software that changes and improves in an evolutionary fashion. This software can be used for limited problems, but it must be treated as a black box.

The same is true for a neural network used for artificial intelligence. It can be trained to recognize something, but that set of interconnections looks nothing like the understandable, maintainable software that humans create.

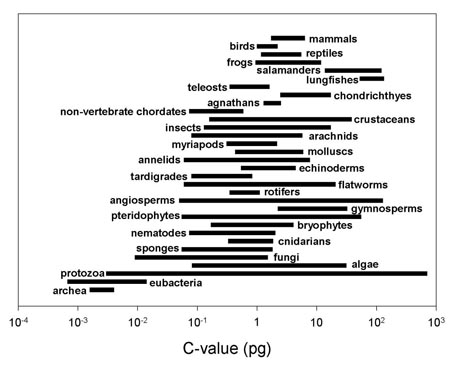

As another illustration of the how DNA is unlike software, the length of an organism’s DNA is not especially proportionate to its complexity. This is the c-value enigma, illustrated with a chart that compares DNA length for many animals here.

We actually have created DNA like a human programmer would create it, at least short segments of it. In 2010, the Craig Venter Institute encoded four text messages into synthetic DNA that was then used to create a living, replicating cell. That’s what a creator who wants to be known does. Natural DNA looks . . . natural. It looks sloppy. It’s complex without being elegant. (See more on the broken stuff in human DNA here and how this defeats the Design Hypothesis here.)

How Would God Program?

If God designed software, we’d expect it to look like elegant, minimalistic, people-designed software, not the Rube Goldberg mess that we see in DNA. Apologists might wonder how we know that this isn’t the way God would do it. Yes, God could have his own way of programming that looks foreign to us, but then the “DNA looks like God’s software” argument fails.

Consider more broadly this supposed analogy between human design and biological systems.

- Human designs have parts purposely put together. We know they are designed because we see the designers and understand how they work.

- Biological systems live and reproduce, and they evolve based on mutation and natural selection.

But these traits of human designs don’t apply to biological systems, and vice versa. So where is the analogy? The only thing they share is complexity, which means that the argument becomes the naïve conclusion, “Golly, biological systems are quite complicated; I guess they must be designed.” This is no evidence for a designer, just an unsupported claim that complexity demands one. And why think complexity is the hallmark of design? Shouldn’t we be looking for elegance instead?

The software analogy leads to uncomfortable conclusions

The DNA = software analogy brings along baggage that the Christian apologist won’t like. The apologist demands, “DNA is information! Show me a single example of information not coming from intelligence!”

This makes them vulnerable to a straightforward retort: Show me a single example of intelligence that’s not natural. Show me a single example of intelligence not coming from a physical brain. These apologists are living in a glass house when appealing to things that have no precedent (and far too comfortable with things that have no evidence, like the supernatural).

Does the Christian imagine multiple Designers of DNA? Because most human designs come from teams. Are those Designers finite? Are they fallible? Were they born? Because these are the properties of human designers (h/t commenter Loren Petrich).

Christians will respond by pointing to the imagined properties of the Christian God, but this is the fallacy of special pleading. They pick the parts of the God/designer analogy they like and dismiss the ones they don’t. This might make it an illustration of God’s properties, but by selecting the parts they like based on their agenda, they make clear that it’s not an argument.

Actually, we find information in lots of nonliving natural things. The frequency components of starlight encodes information about that star’s composition and speed. Tree rings tell us about past precipitation and carbon-14 fluctuation. Ice cores and varves (annual sediment layers in a pond) also reveal details of climate. Smell can tell us that food has gone bad or if a dead animal is nearby. Snowflakes record the atmospheric conditions that created them.

Commenter NS Alito observed:

In my sedimentary geology classes, we used various rock deposition construction patterns to determine the environment in which it was formed, such as preserved ripple structures, proportions of sand vs. clay, silica concretions in sandstone, etc. The various “programmers” of this information were wave energy, upstream eroded material, water chemistry and other natural physical processes.

The popular DNA = software analogy should be discarded for lack of evidence.

is to admit we’re in a naturalistic universe

and thus make the question void.

— commenter primenumbers

.

(This is an update of a post that originally appeared 3/18/17.)

Image from AndreaLaurel (license CC BY 2.0)

.

One popular science-y argument for God is that DNA is information. In fact, it’s not only information, it’s a software program. Programs require programmers, so for DNA, this programmer must be God.

One popular science-y argument for God is that DNA is information. In fact, it’s not only information, it’s a software program. Programs require programmers, so for DNA, this programmer must be God. Dysteleology is the idea that life or nature does not show compelling evidence of design, in contrast to the Christian perception of purpose or design (teleology). Recent discoveries in DNA verify that life looks more haphazard than designed.

Dysteleology is the idea that life or nature does not show compelling evidence of design, in contrast to the Christian perception of purpose or design (teleology). Recent discoveries in DNA verify that life looks more haphazard than designed.